In countries around the world, business and political leaders are having a healthy discussion about the underrepresentation of women on corporate boards. Despite evidence that gender-diverse boards lead to lower volatility and improved performance, women held just 15% of all board seats globally in 2017.

Can gender quotas move the needle?

A large body of global academic research suggests that governments enact a board gender quota if other methods (such as mentoring and target-setting) don’t increase female representation in the highest echelons of a firm. In fact, since 2003, 11 countries have enacted gender quotas. The European Commission also proposed legislation to introduce gender quotas to increase the number of women on the boards of publicly listed companies. (In 2018, California became the first state to introduce quotas requiring publicly traded companies to include women on their boards of directors.)

Yet, there has been startlingly little research done on the efficacy of these laws. Do these enacted policies actually achieve the desired outcomes? Are there negative and unintended consequences?

Ruth Mateos de Cabo of Universidad CEU San Pablo (Madrid), Ricardo Gimeno of Bank of Spain, Loren Escot of Universidad Complutense (Madrid), and I studied Spain’s 2007 law. We developed a 14-year dataset and ran an exhaustive series of tests to determine how well the 2007 Spanish Gender Equality Act’s board gender quota was achieved. Our research data, recently published in the European Management Journal, suggests that the law had no discernible effect.

Spain’s “Soft” Quota

Compared to other European countries, Spain has relatively low rates of female labor market participation, including as managers. The 2007 Spanish Gender Equality Act (Ley de Mujeres) was put forward by then King Juan Carlos who recommended a number of laws to improve women’s position. Articles 75 and 78 of the Act introduced a quota of no less than 40% and no more than 60% of each gender to serve as board directors of the country’s largest and wealthiest firms.

Spain’s law applies to both public and private firms, which would seem to offer maximum impact. The quotas in Norway, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, and other countries only apply to publicly-held firms.

But the Spanish quota is a “soft law,” meaning it has no sanctions for non-compliant firms. Norway’s law, for instance, has a heavy sanction of de-listing from the Oslo Stock Exchange (which did seem to stimulate compliance). Also unlike Norway, Spain’s Act only offers one incentive for quota-compliant firms: the Spanish government can show preference in awarding contracts to them for complying.

The combination of a weak positive incentive and a lack of penalties in the Act may be a reason why board proportions did not rise to the targeted 40%.

The Results

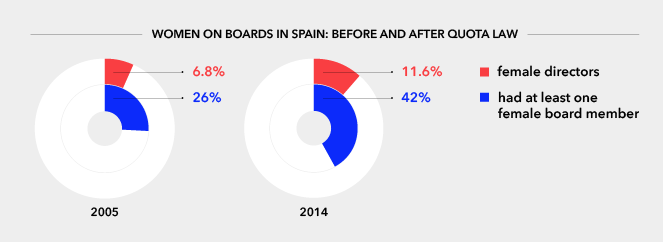

Our research data indicate that in June 2005, 6.8% of directors of Spain’s 767 largest firms (those targeted by the quota) were women, and 26% of these firms had at least one female board member. By 2014, the share of female directors rose only to 11.6% (a 70% increase but very far below the target), and the share of firms with at least one female director rose only to 42%.

We followed up with some “difference-in-differences” tests which can assess the effectiveness of increasing the share of women directors, controlling for a number of relevant factors such as industry, percent of female managers in a given industry, board size, firm size, age, and risk. Taking all these factors into account, and for all Spanish firms, we find no statistically significant difference in the share of female board members appointed after the quota was enacted.

We only find a positive and statistically significant effect for the smaller set of about 75 firms which depend on public contracts—these firms increased their share of female directors by about 4 percentage points in the seven years since the quota was enacted.

Our difference-in-differences tests also allowed us to examine overall quota compliance. Firms overall were not likely to appoint a gender-balanced (according to the Act, at least 40% of each gender) board, but the smaller set of about 75 firms that depend on public contracts were more likely to do so, but less than 5% of these firms actually reached a gender-balanced board. We ran a series of robustness checks using different time frames, unbalanced panels, year dummies, and alternative measures of public sector dependence, and our results still hold.

Did the Quota Improve the Bottom Line?

We also examined whether firms that depend on public contracts and complied with the quota were actually successful in attaining greater income from public contracts.

The answer to this question is no. So not only did the majority of Spanish firms not reach compliance and show no significant change in the share of female board members appointed after the quota, but those few that made the most effort didn’t seem to benefit from the one government incentive offered.

While soft laws are intended to help achieve different forms of gender equality, our research on the effectiveness of the 2007 Spanish Gender Equality Act shows that this soft law has fallen far short of the desired aims. Firms that depend on public contracts increased their share of women by about 4 percentage points, but the whole set of firms only increased their share by about .5 percentage points each year.

Even though the Spanish law appears to have been ineffective, at least we now know that such a weak law is very unlikely to achieve more than very slow progress. And going forward, I encourage researchers to examine if similar legislation actually reaches the goals set forth, especially considering different incentives. Our study covers only one country—imagine what the world could learn by studying the outcomes of equality-driven legislation in every country.

As a Visiting Scholar with Catalyst, Dr. Siri Terjesen contributes research associated with Catalyst’s mission to expand opportunities for women and business. Siri is the Dean’s Distinguished Professor Entrepreneurship at Florida Atlantic University’s College of Business. She is also a Professor .2 at the Norwegian School of Economics. Siri’s research focuses on strategic entrepreneurship, international management, corporate governance, and gender in management, and she has been published in leading journals such as Academy of Management Review, Strategic Management Journal, Journal of Management, Business Ethics Quarterly, Journal of Business Ethics, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, Small Business Economics, Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, Production and Operations Management, and Journal of Operations Management. She is an Associate Editor of Small Business Economics and Industry & Innovation. She has served as Membership Chair for the Academy of Management’s Entrepreneurship Division and Associate Editor for Academy of Management Learning & Education. Siri received her undergraduate education at the University of Richmond, her Masters at the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration in Bergen, Norway as a Fulbright Scholar, and PhD at Cranfield University in the UK. She was a post-doctoral fellow at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia. Prior to starting her academic career, she was a consultant with Accenture. Siri is affiliated with Stockholm’s Ratio Institute and joined Strata’s board in 2016. Prior to her academic career, Siri was a management consultant with Accenture, on projects in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Berlin, Germany. She was also a competitive ultra-distance runner, representing the United States, England, and Queensland (Australia) in international competitions. Her research can be found on Google Scholar and her professional profile on LinkedIn. You can also follow her on Twitter.