Masculine Anxiety and Interrupting Sexism at Work

Sarah DiMuccio, PhD , Negin Sattari, PhD , Emily Shaffer, PhD , Jared Cline

Why don’t men interrupt sexism in the workplace? Past Catalyst research has shown that many men want to intervene and reduce sexism—yet sometimes do not. This study finds that men at work often experience “masculine anxiety”—distress over not living up to society’s rigid masculine standards. The study also reveals that men with high masculine anxiety are likely to say they would do nothing in the face of workplace sexism. Workplace culture plays a large role in levels of masculine anxiety; organizations must recognize masculine anxiety and curb organizational norms that reinforce it.

Masculine Anxiety: An Overlooked Factor in Men’s Reluctance to Interrupt Sexism

Starting from infancy, each one of us is a sponge, absorbing how family members, caretakers, peers, and community members speak about and treat people of different genders. Growing up, the differences and similarities we notice are reinforced by the content that we read, watch, and listen to. Without even realizing it, we usually learn that the world is divided into women and men, girls and boys—with specific characteristics valued for each gender.1

With every observation, we become ever more immersed in the prevailing societal expectations for women and men—which behaviors are encouraged and lead to praise, and which behaviors are discouraged and met with criticism. We incorporate what our culture deems to be masculine and feminine into our mindsets, even though this binary view of gender does not reflect the lived experiences of many people. By the time we reach adulthood, most of us have internalized these principles—whether we want to or not.

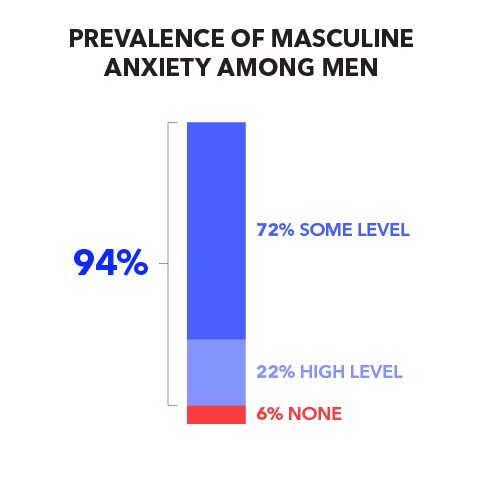

Through this process, men in contemporary US society are put under intense pressure to conform to the ubiquitous messages about what a “real man” looks like, how he behaves, and what he wants. As a result, masculine anxiety, which we define as the distress men feel when they do not think they are living up to society’s rigid standards of masculinity, is widespread. We surveyed over 1,000 men in the United States and found that almost all of them—94%—experience at least some degree of masculine anxiety at work.2

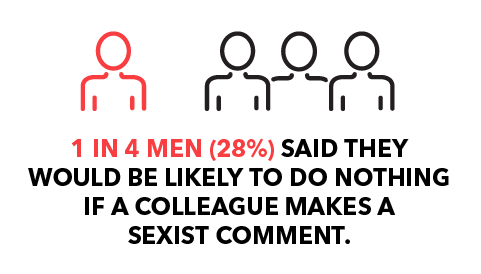

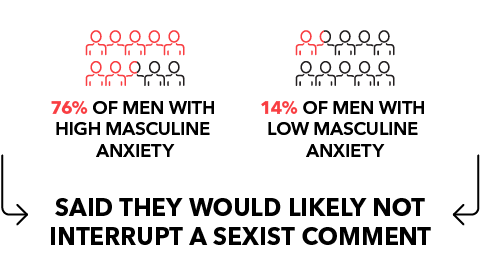

This finding has important implications for organizations that want to confront workplace sexism. Our data show that more than one-quarter of men in our survey (28%) said they would likely do nothing if they heard a colleague make a sexist remark at work—and that masculine anxiety is a major factor in men’s reluctance to interrupt sexism. According to our survey, men who experience high levels of masculine anxiety are five times more likely to do nothing than men who experience less masculine anxiety.

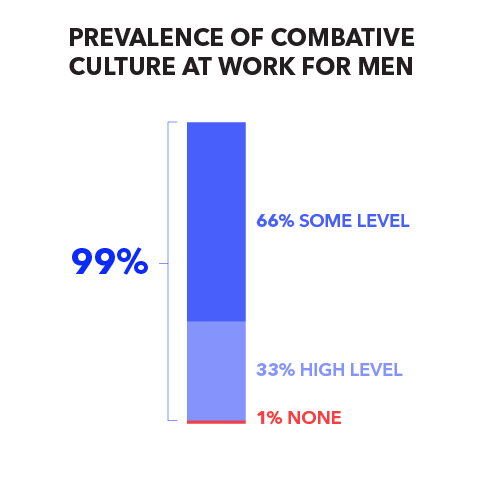

Furthermore, we found that organizational culture can have a strong impact on masculine anxiety and its negative consequences for interrupting workplace sexism. When men work in organizations with a combative culture—where colleagues maneuver to show domination and power through traditionally masculine behaviors—they are more likely to do nothing when they hear a sexist comment at work, and the men most affected by this type of culture are those with high levels of masculine anxiety.

The invisible forces that subtly and effectively dissuade men from acting in ways that might lead others to question their manliness are damaging to people of all genders. Organizations must acknowledge masculine anxiety, talk about it, and address it when planning culture change and gender equity initiatives.

Key Findings

- Masculine anxiety, which is exacerbated by a combative culture at work, is widespread, and it is powerfully linked to men’s decisions not to challenge sexist behavior.

- Nearly all men (94%) said that they experience any level of masculine anxiety, and more than one in five (22%) experience high levels of masculine anxiety at work.

- More than a quarter (28%) of men said that they would be likely to do nothing if their colleague makes a sexist comment at work.3

- The vast majority (76%) of men who experience a high degree of masculine anxiety said that they would do nothing if their colleague makes a sexist comment at work, compared to 14% of men who experience less anxiety about their masculinity.

- Nearly all men (99%) indicated that their workplace has some level of combative culture, and 33% of men said that there is a highly combative culture within their workplace.

- In workplaces with a highly combative culture, 61% of men said they would do nothing, compared to 12% of men who work in less combative workplaces.

- More than half (55%) of men report having a high degree of masculinity anxiety in organizations with a highly combative culture, compared to only 6% of men working in less combative workplaces.

- In more combative cultures, the likelihood of doing nothing if their colleague makes a sexist comment at work increases more sharply for men with high masculinity anxiety than for those with lower levels of masculine anxiety.

About This Study

Interrupting Sexism at Work is a research initiative exploring organizational conditions that encourage or discourage men from responding when they witness incidences of sexism in the workplace. The initiative includes countries in North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific. This report is the third in the series and is based on data from the United States.

Our first study, Interrupting Sexism at Work: How Men Respond in a Climate of Silence, drew on insights from a study conducted in Mexico to highlight the negative impacts of a climate of silence in the workplace on men’s intention to comment on observed sexist behaviors. It showed that men who experience higher levels of silence in their workplace see more costs and fewer benefits in interrupting sexist behaviors in the workplace.4

The second study, Interrupting Sexism at Work: What Drives Men to Respond Directly or Do Nothing?, examined the role that personal agency and organizational conditions play in predicting men’s responses to workplace sexism. In particular, we found that negative organizational environments such as a climate of silence, a climate of futility, and combative culture are responsible for a large portion of men’s intent to do nothing in response to workplace sexism.5

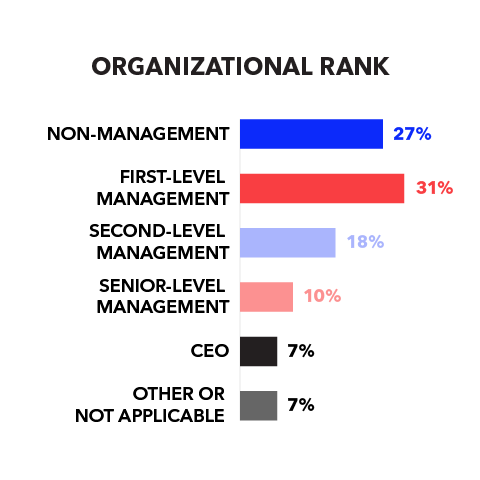

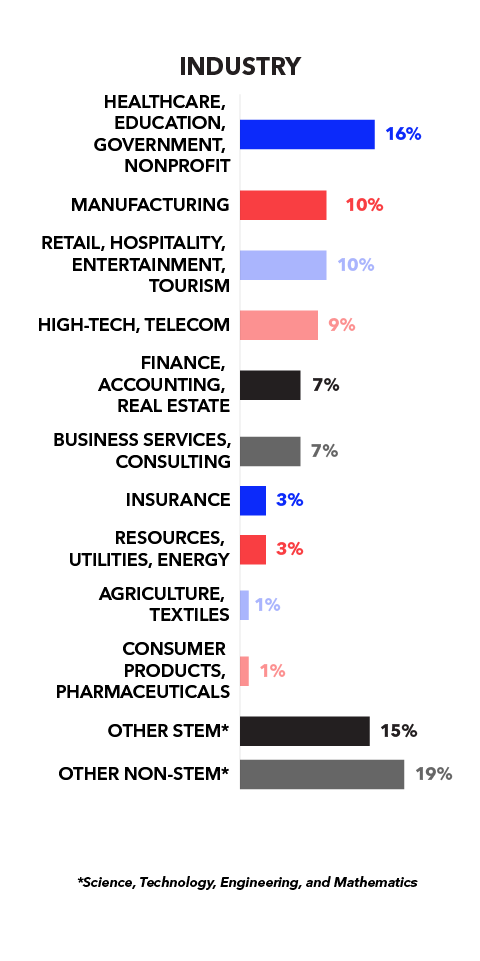

This third study draws from results from a large-scale survey and insights from in-depth interviews. We surveyed 1,007 men who were employed full-time in the US labor market. They represent a diverse group, spanning a range of industries, organizational ranks, job tenure, ages, and ethnic backgrounds.

We also conducted in-depth phone or video interviews with 16 men across industries in the United States. These men shared candid, insightful, and sometimes sobering stories about masculinity, gender equality, and sexism in the workplace, as well as their own views on what it takes to make change.

Please refer to the methodology for more information about the study design.

Companies Must Recognize the Prevalence of Masculine Anxiety

If I were in a [workplace with] more men, I think masculinity would become an absolute pressure where I would feel more required to perform based on manliness than on being a professional or expert.

– Derek, director of marketing11

To measure masculine anxiety, we asked men how stressful they find certain work situations such as showing vulnerability, being viewed as not manly, comforting another man, and having a woman manager. Based on their responses, we found that masculine anxiety is pervasive in US workplaces: 94% of men in our survey said that they experience any level of masculine anxiety at work, and close to one in four—22%—indicated that they experience high levels of masculine anxiety.12

Because nearly all men surveyed experience some degree of masculine anxiety, companies must explore how it plays out in their workplaces and in society to the detriment of everyone.

A substantial body of research has already identified the mechanics of manhood and the consequences of the expectation that men will conform to its strict conventions. Studies show that men in the US experience immense pressure to present themselves as “real men” who are tough, aggressive, sexually assertive, and confident, among other things. “Real men” are also expected to avoid all that is considered feminine, including displays of emotion other than anger.13 Here is how it works:

US society values characteristics associated with masculinity (e.g., achievement, competition, and success) more than those associated with femininity (e.g., care and compassion).14 Men who conform to these masculine norms show themselves to be “real men” and are rewarded with status and privilege.

- Men who deviate from the prescribed behavior know their manliness may be questioned and that they may be punished by other men and by women with loss of their status as a “real man.”

Manhood is difficult to achieve and easily lost. Because men’s work proving their status as “real men” is never fully done, masculinity is precarious.

- Men who fail to appear manly enough are likely to feel threatened by a loss not just of status, but also a sense of their own manliness.15

- Socially, men face stigma and backlash if they are perceived as insufficiently masculine.16

- It is not easy to ignore these consequences: A Pew Research Center survey suggests that more than half of US adults believe society looks up to men who demonstrate traditionally masculine characteristics.17

These deeply embedded social norms lead to a host of negative consequences for both men and women.

- Research suggests that higher rates of suicide,18 mental health problems,19 and poor health behaviors20 among men may be explained by rigid standards of masculinity.

- Men with stronger beliefs that manhood should constantly be proved (through traditionally masculine behavior) are at greater risk of health problems caused by the stress of potentially losing their masculine status21 and are less likely to seek help.22

- Such beliefs also increase the likelihood that men use sexist or homophobic humor to bolster their manliness23 and reduce their likelihood of confronting sexual prejudice.24

Central to this report, research shows that the discomfort and stress men feel when they think they have failed to appear sufficiently masculine—what we call masculine anxiety—is associated with and causes more intimate partner violence25 and aggression,26 increased support for benevolent sexism,27 decreased support for gender equality, and greater acceptance of group-based inequality that oppresses women and gay men.28 These consequences are serious, dangerous, and harmful to a healthy and equitable society.

Masculine Anxiety is Related to Men’s Decisions to Interrupt Sexism

Since sexism is a problem that affects organizations and teams as a whole, everyone needs to take responsibility to eliminate it from the culture, not just the people who directly suffer from it. In fact, in many instances, men are better situated than women to interrupt sexism. Not only are men rarely targets of sexism, but they also face fewer negative consequences than women when they interrupt instances of sexism29 and are less discouraged by such social costs.30 For women who choose to confront sexist acts at work, research shows that there are benefits,31 but there also can be high costs.32

So it’s troubling that more than one-quarter (28%) of men we surveyed said they would be likely to do nothing if their colleague makes a sexist comment at work. For organizations with programs to prevent and eliminate sexism, success depends on encouraging these men to respond to sexism differently.

But to drive this change, we must first understand what lies behind men’s decisions to do nothing when confronted with sexism at work and identify potentially overlooked costs to men of interrupting sexism. Previous research has shown that various factors influence whether and how men will respond to incidences of sexism. For example, external studies have identified individual-level characteristics such as personal beliefs, skills, and mindsets,33 while the previous Catalyst reports in this series showed that men’s responses to workplace sexism are affected by organizational conditions.

Our data indicate that another factor, masculine anxiety, exerts an outsized influence on men’s decisions. We found that 76% of men who experience a high degree of masculine anxiety said that they would do nothing in response to a sexist comment at work, whereas only 14% of men who experience less anxiety about their masculinity said they would do nothing.34 This shows that for men who are concerned about behaving in ways that lead others to question their masculinity, speaking up against sexism can be perceived as attesting to their potentially flawed manliness.

This finding is crucial because it means that organizational interventions such as trainings and awareness-raising programs that encourage men to engage in gender partnership and advocacy may not translate into action by men experiencing masculine anxiety to interrupt sexism. By making meaningful change in how men understand and experience their masculinity, organizations can confront one of the root causes of both workplace sexism and men’s inaction.

Masculine Anxiety Increases for Managers

Interestingly, we found that managers (32%) were more likely than non-managers (17%) to indicate they would do nothing in response to workplace sexism.35 We also found that managers (29%) were more likely than non-managers (9%) to experience high masculine anxiety.36 In other words, more power brings more anxiety, which may be felt as increased pressure to live up to masculine ideals and more to lose if men don’t live up to those ideals.

This finding is important since managers uniquely set the tone for team culture37 and are instrumental in creating an environment where people feel comfortable calling out sexism, microaggressions, and other types of inequities. Ultimately, it is essential for organizational culture change initiatives to target employees at every level to be successful.

Take Action: Start Conversations About Masculine Anxiety

The more men are able to identify, acknowledge, and unpack their masculine anxiety, the less this anxiety might lead to behavior that could harm themselves and others. To help men through this self-reflection, organizations can create environments where men feel comfortable exploring their masculinity and how it affects their lives.

Use the questions below to start candid conversations with men about what masculine anxiety feels like and workplace situations where it might show up.

To what extent do you identify with any of the following statements?

- “I’m afraid to appear weak or indecisive.”

- “I feel pressure to like ‘guy stuff’ or be left out.”

- “Other people can tell I’m not ‘one of the guys.’”

- “I compare myself to other men and feel like I come up short.”

- “Will I be noticed if I’m not as masculine as other men?”

To what extent, if at all, would you feel anxious in the following situations?

- Providing emotional support to another man at work.

- Sharing your fears about a work assignment.

- Seeing a woman get a promotion you wanted.

- Reporting to a manager who is a woman.

- Admitting you can’t do something alone.

- Being vulnerable with other men.

Combative Cultures and Masculine Anxiety: A Potent Mix

Some workplace cultures tap into men’s anxiety about their masculinity, using it as a lever to ratchet up displays of manliness. We call these “combative cultures,”38 and research—including a previous report in this series39—has described them as places where employees gain professional success when they are able to outperform others in a competition for power, authority, and status that rewards stereotypically masculine behaviors.40

To be a “winner” in a combative culture, people—of all genders—must show strength and stamina, put work ahead of all else, and advocate only for themselves. People who show any kind of weakness or vulnerability or who prioritize personal issues or family will quickly be characterized as “losers.”

This type of culture exacerbates masculine anxiety and the fear of appearing unmanly. Because one “wrong” comment or decision can so easily result in a man’s masculinity being called into question,41 many men are in a perpetual state of threat—and seek to defend themselves by proving again and again how masculine, and therefore worthy, they are.42

In our survey, 99% of men said that there is at least some degree of combative culture in their workplace, and 33% of respondents indicated high levels of combative culture at work.43

Perhaps not surprisingly, working in a highly combative culture predicts both high masculine anxiety and the likelihood that men will do nothing when they witness a sexist comment at work.

% of men with high masculine anxiety in:

highly combative cultures

less combative cultures44

% of men who would do nothing to interrupt sexism at work in:

highly combative cultures

less combative cultures45

Notably, we found that a combative culture is linked to all men’s likelihood of doing nothing if they hear a sexist comment at work. In other words, both men with low masculine anxiety and men with high masculine anxiety were more likely to do nothing if they worked in a combative culture. Interestingly, although we found this link for all men, its strength differed by men’s degree of masculine anxiety.46

- Men with higher levels of masculine anxiety are 12 times more likely to do nothing if they work in a highly combative culture compared to a less combative culture.47

- Men with lower levels of masculine anxiety are four times more likely to do nothing if they work in a highly combative culture compared to a less combative culture.48

These findings suggest that combative cultures contribute to masculine anxiety, and that the behavioral norms they espouse can be powerful enough to: 1) shape the behavior of men who, on average, don’t feel a lot of masculine anxiety, and 2) severely deter men more prone to masculine anxiety.

This potent combination of forces should be a major target for organizations focused on increasing gender equity.

The Many Dimensions of Dysfunction in Combative Cultures

As we’ve seen, highly combative cultures are the reality for one in three men in our survey. Combative cultures are dysfunctional in many ways and should be reined in by organizational leaders.49 Research finds that:

- Employees who believe that their colleagues support a combative culture are less likely to speak up against it even if they quietly reject it.50

- When employees believe that their colleagues’ support for a combative culture is greater than their own, they experience decreased job satisfaction, decreased mental health, and increased relationship conflict.51

- Workplaces with a combative culture are associated with harmful organizational dynamics including domineering coworker behaviors like bullying and harassment, burnout, intent to leave, and poor personal well-being.52

- Combative cultures create conditions in which toxic patterns of leadership are more likely to thrive. Toxic leadership and combative cultures both contribute to “lower work engagement, lower meaningfulness, work/family conflicts, stress,” and turnover intentions.53

Actions to Quash Combative Cultures: Insights From Interviews

Our data clearly show that combative cultures that exploit and encourage men’s anxieties must be quashed in order to make progress on gender equity. The men we interviewed identified a range of issues that point to concrete actions organizations can take.

Make caregiver leaves gender-free

In many workplaces, people assume and expect that men will take far shorter caregiver leaves than women. Encourage men to take full advantage of company leave policies and showcase leaders who model this behavior.

As much as women are often excluded from the workplace…I would say that men are excluded from the parenting process…especially in more traditional ideas of parenting.

– Austin, Social Services Manager

Make it okay to admit failure

Men experiencing masculine anxiety may find it difficult to ask for help or admit they’ve failed, especially in a dog-eat-dog environment. Train leaders to be more inclusive, so employees have the psychological safety to admit making mistakes without being penalized.

Work happens at the speed of trust….If there’s no trust, it’s going to take you forever….Let people go do their thing, fail, and come back.

– Diego, Nonprofit Advisor

Give permission to do something differently

Pressure to be “one of the guys” is a prominent feature of combative cultures. Clearly communicate inclusive values to equip individuals with the permission they need to respectfully propose different alternatives and ideas.

There’s an expectation that, you know, we go golfing, we go shooting, we go drinking [with clients]. And so…it takes a lot of courage to start drawing lines in the sand and say we are going to have a different kind of event.

– James, Director in STEM Industry

Recognize that everyone is influenced by combative culture

In combative climates, everyone lives or dies by the same dominance-based rules. This applies to men as well as women. Commit to deeply analyzing your organizational culture to identify how to decrease competition and work-first thinking in employees of all genders.

There’s a big assumption that when you have more women in leadership positions [the environment] for everybody is better. In some ways, it’s true. [But] in some spaces, it’s very patriarchal—it replicates those same ways of behaving, of acting, and of decision making. [I thought] if we had more women [leaders], things were going to be different, but they’re not changing.

– Diego, Nonprofit Advisor

Diversify the working environment

In noncombative cultures, men are freer to be themselves because they don’t feel constant pressure to prove their manhood. Diversify your teams and encourage employees to work across teams to gain new perspectives.

When I was part of the [majority group] that has more power, that’s when I felt silenced….When I was part of the minority in a different organization, that’s when I felt most free to share my opinions.

– Austin, Social Services Manager

Embed advocacy for others into the culture

In an environment where it feels like it’s “every man for himself,” some men may feel that they have to choose between advocacy and getting ahead at work. Incorporate employee advocacy into professional development goals to create a culture where this false choice doesn’t exist.

The journey that I’m on is trying to […] get to where I need to be in my career before I can really advocate [for women]. […] It’s a hard place to be in for a man who wants to be supportive, but also has personal goals. And that fear of losing that to, to support others, it’s just a hard place to be.

– Alex, Entry-Level Technology Representative

Strategic Solution:

Improve Workplace Fairness

Our data point to a strategy companies can use to combat sexism at work.

For men with high masculine anxiety, workplace fairness—whether people think they and others are treated fairly—can be especially transformative, becoming a strong counterweight to their powerful inclination not to challenge a sexist comment at work.54 Workplace fairness may also diminish negative outcomes from other organizational problems such as combative cultures.55

Only 54% of men characterized their workplace as high in fairness,56 but those that did were far less likely to have high masculine anxiety and to do nothing when they observe workplace sexism.

% of men experiencing a high level of masculine anxiety in:57

more fair organizations

less fair organizations

% of men who said that they would do nothing when they heard a sexist comment in:58

more fair organizations

less fair organizations

The striking effect of organizational fairness complements prior Catalyst research on engaging men in gender initiatives, which showed that a strong sense of fair play was shared by many men who actively championed gender equality at work.59

To encourage and display fairness at work, start with the following steps:

- Increase transparency: Develop clear and consistent policies and procedures so that people know, for example, what it takes to be promoted, what the chain of approval is, and what behavior is off limits.

- Clarify expectations: Employees need to know ahead of time how they will be assessed for performance, behavior, and teamwork.

- Share resources equitably: Make sure that resources aren’t concentrated with a few favored employees or teams. This includes tangible things like budget, staff, and equipment as well as intangibles like new opportunities and information for a project.

- Communicate inclusively: Ensure that language isn’t displaying biases. For example, use gender-neutral words in job descriptions and watch out for words or phrases that might reveal unconscious biases.

- Encourage humility: No person or team is perfect. A culture that acknowledges and learns from mistakes demonstrates that feedback is valuable.

- Listen to employees: Reach out through anonymous surveys, focus groups, and one-on-one meetings to identify “pain points” and identify solutions.

Methodology

Data Collection and Sample

This study relies primarily on a quantitative approach using survey data. We conducted qualitative interviews in parallel to inform our thinking about how men’s behavior in the workplace is influenced by organizational conditions. The quotations in the report are from these interviews.

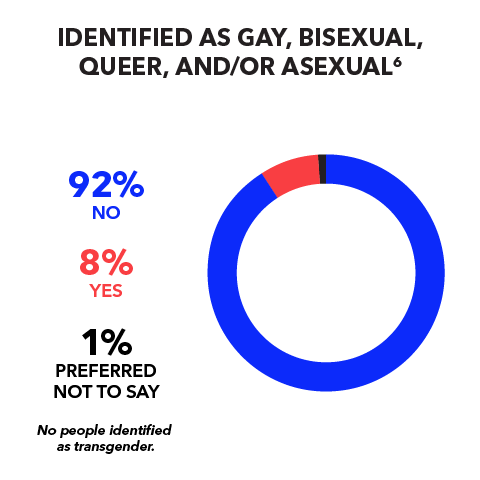

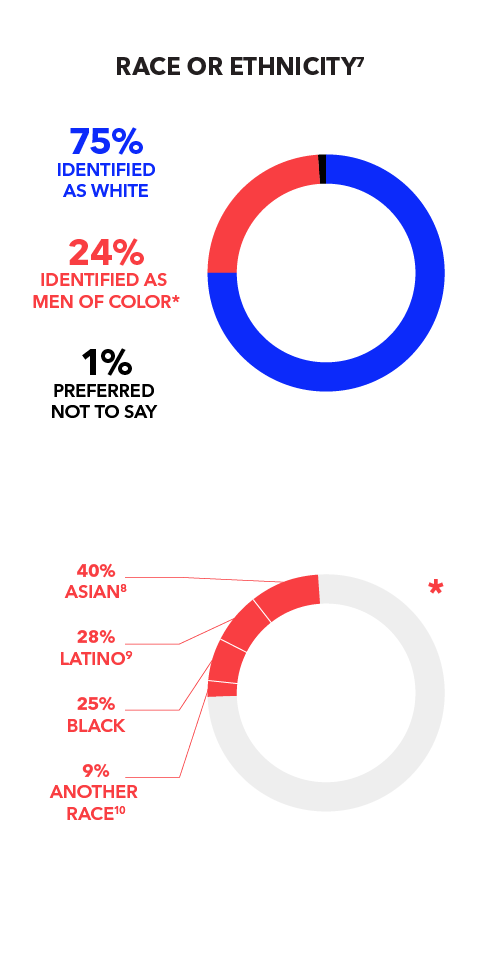

An online survey about experiences with sexism in the workplace was completed by 1,007 men working in the United States. Participants were eligible to participate in the survey if they lived in the US, identified as a man, and were employed on a full-time basis. The average age of participants was 43 years old. Of the sample, 75% of participants chose White as their only racial or ethnic identity and 24% included at least one underrepresented racial or ethnic group in their responses; 1% preferred not to disclose their race or ethnicity. No people identified as transgender, 8% identified as gay, bisexual, queer, and/or asexual, and 1% preferred not to say.

Survey Content: Survey questions examined men’s (1) perceptions of their organizational climate (perceived combative culture and organizational fairness) and their work experiences; (2) level of masculine anxiety experienced in the workplace (3) perceptions of the consequences of interrupting sexism in their workplaces; (4) behavioral intentions in response to incidences of sexism in the workplace; and (5) gender ideology beliefs and level of commitment to removing gender inequity.

Understanding Masculine Anxiety: Masculine role anxiety was measured in two ways. First, it was measured using a modified version of the five-item Gender Role Discrepancy Stress Scale60 as a measure of stress that “arises when a man believes that he is, or believes he is perceived to be insufficiently masculine.” Some of the items were adapted to refer to an organizational context.

Second, we used an abbreviated version of the Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale,61 which is meant to measure the stress that men feel when situations arise that are challenging to hegemonic notions of masculinity. We used typical work-related situations. Respondents were asked to indicate how stressful (on a six-point scale from not at all stressful to extremely stressful) they found the following six scenarios: comforting a male colleague who is upset, admitting that you are afraid of something, being outperformed at work by women, having a woman boss, having to ask for help, and talking about your feelings with other men.

Individual alphas for both of these scales were good (Cronbach’s alpha for both scales were greater than 0.9) and they were highly correlated (r = 0.795, p < 0.001) with one another, so they were collapsed to create a single measure of “masculine anxiety” by averaging all the items.

Men who score high on the scale feel more anxiety surrounding societal expectations to both be perceived as, and perform masculinity, sufficiently. This method of operationalizing masculine anxiety is important to highlight, because it is not simply adherence to masculine norms, nor is it how masculine men believe themselves to be. Rather, it is a measure of the stress or anxiety associated with societal pressures for men to appear and behave in very specific ways. If a man is anxious that he is not living up to these expectations, it would also be particularly stressful for him to be put into situations in the workplace that further exacerbate these worries (namely, having to show emotions or weakness to male colleagues, or having to answer to woman colleagues). Scale responses ranged from 1 (no masculine anxiety) to 6 (extreme anxiety). The percentages presented in this study reflect scores higher than 1.

Analysis: We analyzed the data using descriptive statistics, correlation, linear regression, and moderation analysis in IBM SPSS Statistics version 25. Where relevant, all results presented were significant at p < .01 unless otherwise noted.

In-depth Interviews: Procedures and Analysis

Format: A Catalyst staff member conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with 16 men in the US labor market; some of the participants were actively engaged in gender advocacy efforts in their workplaces, and some were not.

Recruitment and Sample: We used social media posts and snowballing sampling to recruit the participants. Those who worked in upper- and senior-level management positions represented 56% of the sample; 38% were mid-level managers, and 6% were in non-managerial positions. The average age of participants in this in-depth interview sample was 41 years old. A majority of the interviewees identified as White, and equal numbers of participants identified as Black, Latinx, and Middle Eastern or Arab. Participants with less than six years of tenure at their current organizations comprised 31%, and 19% had more than 20 years of tenure. Interviewees came from diverse industries with 50% from manufacturing, consumer goods, and energy; 31% from technology, marketing, sciences, and finance; and 19% from social services and nonprofits.

Interview Content: Our interview questions were purposefully designed to encourage participants to reflect on contextual factors in organizations that can have either enabling or disempowering implications for men’s ability to engage in workplace gender equity initiatives and actively interrupt sexism.

Interview topics included: (1) discussion of participants’ backgrounds and engagement in gender advocacy both inside and outside the workplace; (2) perceptions of workplace conditions that can promote sexism; (3) experiences with interrupting sexism and organizational factors impacting those experiences; and (4) suggestions for how organizations can encourage men to advocate for gender equity as well as ideas for effectively interrupting sexism.

Analysis of Interview Data: All the interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ consent and were transcribed verbatim for analysis using online, automatic transcription software. These transcriptions were then double-checked for accuracy by Catalyst staff. Audio files were permanently deleted after transcription was completed. Any identifying information including participants’ real names and their current or previous workplaces was removed from all the transcripts. Interviews were then coded in NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software package, by two team members to identify the narratives that alluded to the impact of masculine cultures and social constructions of masculinity on men’s engagement in interrupting sexism and gender advocacy more generally.

Acknowledgments

We thank our donors for their generous support of our work in this area:

MARC (Men Advocating Real Change)

KeyBank

Northrop Grumman

Sodexo SA

JPMorgan Chase & Co.

How to Cite: DiMuccio, S., Sattari, N., Shaffer, E., & Cline, J. (2021). Masculine anxiety and interrupting sexism at work. Catalyst.

Endnotes

- For a more in-depth review of gender and its influences on our lives, see Sattari, N., Pollack, A., & Gallien, A. (2019). What is gender? A tool to understand gender identity. Catalyst.

- Masculine role anxiety was measured by using a modified version of the five-item Gender Role Discrepancy Stress Scale developed by Reidy, D. E., Berke, D. S., Gentile, B., & Zeichner, A. (2014). Man enough? Masculine discrepancy stress and intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 160-164. We also used an abbreviated version of the Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale originally developed by Eisler, R. M. & Skidmore, J. R. (1987). Masculine gender role stress: Scale development and component factors in the appraisal of stressful situations, Behavior Modification, 11(2), 123-136. See the methodology for more information.

- In Catalyst’s study, Interrupting Sexism at Work: What Drives Men to Respond Directly or Do Nothing, we developed and validated a comprehensive measure of intended interrupting behaviors after the hearing of a sexist remark. Four distinct behaviors were identified. The same scale and subscales were used in this study with a particular focus on “doing nothing” behaviors.

- Shaffer, E., Sattari, N., & Pollack, A. (2020). Interrupting sexism at work: How men respond in a climate of silence. Catalyst.

- Sattari, N., Shaffer, E., DiMuccio, S., & Travis, D. J. (2020). Interrupting sexism at work: What drives men to respond directly or do nothing? Catalyst.

- Percentages add up to slightly more than 100% due to rounding.

- Participants had the option to choose more than one racial and/or ethnic category; 76% identified as only White and 24% selected at least one of the underrepresented race or ethnic categories as part of their identity.

- Represented groups in this category are Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Other Latinx.

- Represented groups in this category are Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Other Asian.

- Represented groups in this category are Arab, Native American or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, and “some other race.”

- Names have been changed to protect confidentiality. Quotations have been lightly edited to remove filler words and phrases such as “like” and “you know.”

- Scale responses ranged from 1 (no masculine anxiety) to 6 (extreme anxiety). The percentages presented reflect scores greater than 1 (at least some anxiety) and those equal or greater than 4 (high levels of anxiety).

- DiMuccio, S. H., Yost, M. R., & Helweg-Larsen, M. (2017). A qualitative analysis of perceptions of precarious manhood in US and Danish men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 18(4), 331–340.

- Country Comparison. (n.d.) Hofstede Insights.

- Schrock, D. & Schwalbe, M. (2009). Men, masculinity, and manhood acts. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 277–295.

- Rudman, L.A. & Mescher, K. (2013). Penalizing men who request a family leave: Is flexibility stigma a femininity stigma? Journal of Social Issues, 69, 322-340; Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan J. E., & Rudman, L.A. (2010). When men break the gender rules: Status incongruity and backlash against modest men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 11, 140-151.

- Horowitz, J. M. (2019). Americans’ views on masculinity differ by party, gender, and race. Pew Research Center.

- Granato, S. L., Smith, P. N., & Selwyn, C. N. (2015). Acquired capability and masculine gender norm adherence: Potential pathways to higher rates of male suicide. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 16(3), 246-253.

- Wong, Y. J., Ho, M.-H. R., Wang, S.-Y., & Miller, I. S. K. (2017). Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 80–93.

- Verdonk, P., Seesing, H., & de Rijk, A. (2010). Doing masculinity, not doing health? A qualitative study among Dutch male employees about health beliefs and workplace physical activity. BMC Public Health, 10, 712.

- Himmelstein, M. S., Kramer, B. L., & Springer, K. W. (2019). Stress in strong convictions: Precarious manhood beliefs moderate cortisol reactivity to masculinity threats. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 20(4), 491–502.

- For a review, see Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58(1), 5-14.

- O’Connor, E. C., Ford, T. E., & Banos, N. C. (2017). Restoring threatened masculinity: The appeal of sexist and anti-gay humor. Sex Roles, 77, 567-580.

- Kroeper, K. M., Sanchez, D. T., & Himmelstein, M. S. (2014). Heterosexual men’s confrontation of sexual prejudice: The role of precarious manhood. Sex Roles, 70, 1-13.

- Reidy, D. E., Berke, D. S., Gentile, B., & Zeichner, A. (2014). Man enough? Masculine discrepancy stress and intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 160-164.

- Stanaland, A., & Gaither, S. (2021). “Be a man”: The role of social pressure in eliciting men’s aggressive cognition. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

- Dahl, J., Vescio, T., & Weaver, K. (2015). How threats to masculinity sequentially cause public discomfort, anger, and ideological dominance over women. Social Psychology, 46, 242-254. In this study, Benevolent sexism refers to stereotypical attitudes about people based on their gender that may be perceived as positive (e.g., the belief that women are more compassionate).

- Weaver, K. S, & Vescio, T. K. (2015). The justification of social inequality in response to masculinity threats. Sex Roles, 72, 521-535.

- Eliezer, D. & Major, B. (2012). It’s not your fault: The social costs of claiming discrimination on behalf of someone else. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15(4): 487-502.

- Good, J. J., Sanchez, D. T., & Moss-Racusin, C. A. (2018). A paternalistic duty to protect? Predicting men’s decisions to confront sexism. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(1), 14-24.

- Gervais, S. J., Hillard, A. L., & Vescio, T. K. (2010). Confronting sexism: The role of relationship orientation and gender. Sex Roles, 63, 463–474; Hyers, L. L. (2007). Resisting prejudice every day: Exploring women’s assertive responses to anti-Black racism, anti-Semitism, heterosexism, and sexism. Sex Roles, 56, 1-12; Rattan A. (2018). Confronting a biased comment can increase your sense of belonging at work. Harvard Business Review.

- Becker, J. C., Glick, P., Ilic, M., & Bohner, G. (2011). Damned if she does, damned if she doesn’t: Consequences of accepting versus confronting patronizing help for the female target and male actor. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 761–773; Swim, J. K., & Hyers, L. L. (1999). Excuse me—What did you just say?!: Women’s public and private responses to sexist remarks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 68–88.

- See, for example, Estevan-Reina, L., de Lemus, S., & Megías, J. L. (2020). Feminist or paternalistic: Understanding men’s motivations to confront sexism. Frontiers in Psychology, 10; Gervais, Hillard, & Vescio (2010); Stewart, A. L. (2014). The Men’s Project: A sexual assault prevention program targeting college men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(4), 481–485.

- Simple regression analysis was carried out to investigate the impact of masculine anxiety level on men’s intent to do nothing in response to a sexist comment. Results indicated that the model was a significant predictor of doing nothing, R2 = 0.51, F (1, 1006) = 1056.6, p < .001. Masculine anxiety (b = .67, t = 32.5, p < .001), significantly predicted doing nothing in response to workplace sexism. A chi-squared analysis was conducted to test the difference in percentages. The observed values were significantly different than expected values, X2 (1) = 329.76, p <.001.

- A chi-squared analysis was conducted to test the difference in percentages. The observed values were significantly different than expected values, X2 (1) = 22.18, p <.001.

- A chi-squared analysis was conducted to test the difference in percentages. The observed values were significantly different than expected values, X2 (1) = 42.00, p <.001.

- Yohn, D .L. (2021). Company culture is everyone’s responsibility. Harvard Business Review.

- Combative culture was measured using the Masculinity Contest Culture scale. Glick, P., Berdahl, J. L., & Alonso, N. M. (2018). Development and validation of the Masculinity Contest Culture Scale. Journal of Social Issues, 74(3), 449–476.

- Sattari, N., Shaffer, E., DiMuccio, S., & Travis, D. J. (2020). Interrupting sexism at work: What drives men to respond directly or do nothing? Catalyst.

- Berdahl, J. L., Cooper, M., Glick, P., Livingston, R. W., & Williams, J. C. (2018). Work as a masculinity contest. Journal of Social Issues, 74(3), 422–448.

- Berdahl et al., (2018).

- Vandello, J. A., & Bosson, J. K. (2013). Hard won and easily lost: A review and synthesis of theory and research on precarious manhood. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(2), 101–113.

- Combative culture was measured with 12 items, which were averaged to create a composite and then dichotomized. Scale responses ranged from 1 (“not at all true of my work environment”) to 6 (“entirely true of my work environment”). The percentages presented reflect scores averaging greater than 1 (at least some level of combative culture experienced) and 4 or higher (high level of combative culture experienced).

- Simple regression analysis was carried out to investigate the impact of combative culture on men’s level of masculine anxiety. Results indicated that the model was a significant predictor of masculine anxiety, R2 = 0.45, F (1, 1006) = 831.84, p < .001. Combative culture (b = .76, t = 28.84, p < .01) significantly predicted masculine anxiety. A chi-squared analysis was conducted to test the difference in percentages. The observed values were significantly different than expected values, X2 (1) = 308.27, p <.001.

- Simple regression analysis was carried out to investigate the impact of combative culture on men’s intent to do nothing in response to a sexist comment. Results indicated that the model was a significant predictor of doing nothing, R2 = 0.39, F (1, 1006) = 652.31, p < .001. Combative culture (b = .66, t = 25.54, p < .001), significantly predicted doing nothing in response to workplace sexism. A chi-squared analysis was conducted to test the difference in percentages. The observed values were significantly different than expected values, X2 (1) = 269.81, p <.001.

- A moderation analysis was performed to examine the impact of a combative culture, masculine anxiety, and their interaction on doing nothing. The overall model was significant, R2 = .58, F (4, 1002) = 344.35, p < .0001. The main effect of combative culture was significant, b = .31, t = 10.49, p < .0001. The main effect of masculine anxiety was also significant, b = .45, t = 16.37, p < .0001. These main effects were qualified by a significant interaction, b = .12, t = 6.99, p < .0001. Simple slopes indicated that where masculine anxiety is high, the link between combative culture and doing nothing is exacerbated. When masculine anxiety is high, b = .47, t = 11.94, p < .0001; but when masculine anxiety is low, b = .15, t = 4.15, p < .0001.

- Binomial logistic regression was performed for men with a high level of masculine anxiety to examine the impact of combative culture on the likelihood of doing nothing in response to a sexist comment. The logistic regression model was statistically significant: X2 (1) = 43.53, p <.001. The model explained 26.4% (Nagelkerke R Square) of variance in the likelihood of doing nothing among respondents. Those who experienced higher levels of combative cultures had 12 times higher odds to do nothing than those experiencing lower levels of combative culture.

- Binomial logistic regression was performed for men with a low level of masculine anxiety to examine the impact of combative culture on the likelihood of doing nothing in response to a sexist comment. The logistic regression model was statistically significant: X2 (1) = 36.95, p <.001. The model explained 8.3% (Nagelkerke R Square) of variance in the likelihood of doing nothing among respondents. Those who experienced higher levels of combative cultures had four times higher odds to do nothing than those experiencing lower levels of combative culture.

- How combative cultures prevent men from interrupting sexism. (2020). Catalyst.

- Munsch, C. L., Weaver, J. R., Bosson, J. K., & O’Connor, L. T. (2018). Everybody but me: Pluralistic ignorance and the masculinity contest. Journal of Social Issues, 74(3), 551–578.

- Munsch et al., (2018).

- Alonso, N. (2018). Playing to win: Male–male sex based harassment and the masculinity contest. Journal of Social Issues, 74(3), 477–499; Glick, Berdahl, & Alonso (2018); Workman-Stark, A. (2020). Countering a masculinity contest culture at work: The moderating role of organizational justice. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 24(1).

- Matos, K., O’Neill, O., & Lei, X. (2018). Toxic leadership and the masculinity contest culture: How “win or die” cultures breed abusive leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 74(3), 500–528.

- A moderation analysis was performed to examine the impact of a perceived organizational fairness, masculine anxiety, and their interaction on doing nothing. The overall model was significant, R2 = .53, F (4, 1002) = 287.86, p < .0001. The main effect of perceived organizational fairness was significant, b = -0.13, t = -4.82, p < .0001. The main effect of masculine anxiety was also significant, b = .6, t = 23.49, p < .0001. These main effects were qualified by a significant interaction, b = -.09, t = -4.66, p < .0001. Simple slopes indicated that where masculine anxiety is high, perceived organizational fairness makes a stronger impact to reduce men’s intent to do nothing. When masculine anxiety is high, b = -0.26, t = -5.97, p < .0001; but when masculine anxiety is low, b is non-significant.

- Workman-Stark (2020).

- Perceived organizational fairness was measured using the Perceived Organizational Justice scale. Ambrose, M. L. & Schminke, M. (2009). The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: A test of mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 491–500.

- Simple regression analysis was carried out to investigate the impact of perceived organizational fairness on men’s level of masculine anxiety. Results indicated that the model was a significant predictor of masculine anxiety, R2 = 0.27, F (1, 1005) = 371.42, p < .001. Perceived fairness (b = -0.58, t = -19.27, p < .001) significantly predicts masculine anxiety in the workplace; as perceived fairness increases, masculine anxiety decreases. A chi-squared analysis was conducted to test the difference in percentages. The observed values were significantly different than expected values, X2 (1) = 162.93, p <.001.

- Simple regression analysis was carried out to investigate the impact of perceived organizational fairness on men’s intent to do nothing in response to a sexist comment. Results indicated that the model was a significant predictor of doing nothing, R2 = 0.19, F (1, 1005) = 251.4, p < .001. Perceived organizational fairness (b = -.46, t = -15.9, p < .001) significantly predicts doing nothing in response to workplace sexism; as perceived fairness increases, propensity to do nothing decreases. A chi-squared analysis was conducted to test the difference in percentages. The observed values were significantly different than expected values, X2 (1) = 171.8, p <.001.

- Prime, J. & Moss-Racusin, C. A. (2009). Engaging men in gender initiatives: What change agents need to know. Catalyst.

- Reidy, D. E., Berke, D. S., Gentile, B., & Zeichner, A. (2014). Man enough? Masculine discrepancy stress and intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 160-164.

- Eisler, R. M. & Skidmore, J. R. (1987). Masculine gender role stress: Scale development and component factors in the appraisal of stressful situations, Behavior Modification, 11, 123-136.